The Tale of SOUTH PACIFIC

James A Michener

|

In 1958 South Pacific, one of the most successful movie musicals of all time opened. The film version of their smash-hit stage show would become, perhaps, the most affectionately regarded of the Rodgers and Hammestein collaborations - and indeed was already much loved by its theatre going audiences around the world with an enthusiasm that would only be eclipsed by their later production of The Sound of Music.

But the story of this lush, romantic, wartime South Sea Island musical spectacular has a most unlikely beginning - in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where New York-born James Albert Michener was growing up in the care of a kindly lady named Mabel Michener, along with eight or nine other waifs and strays that she had taken in. Always vague about the year of his birth - it would probably have been around 1907 - he claimed February 3rd as his Birthday. In later years, Michener would state that he never knew his parents, though many now believe that Mabel Michener was, in fact, his biological mother.

They lived in dire poverty, often moving house at short notice because Mabel earned a living cleaning and renovating properties for real estate agents, some of which they would be permitted to live in until they were sold. In spite of this, Mabel instilled into her brood a love of books and reading, and by the age of 14, the highly intelligent - and fiercely independent - James Michener had hitchhiked through several states, penniless and without possessions of any kind except the clothes he stood up in, in search of adventure. From these early expeditions came Michener's life-long love of travel and the history of various cultures and societies, which would provide the inspiration for the forty-odd best-selling novels he would write in his long career.

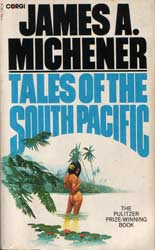

He continued his travels around America for the next few years, sustaining himself with a variety of jobs, including working in a carnival show. Before he was 20, he had visited all but three States of the Union. Graduating, Summa Cum Laude, from Swarthmore College, in 1929 he attended Colorado State Teacher's College, where he obtained his Master's Degree. Remaining to teach there for several years, he also became a Visiting Professor of History at Harvard University, and an editor of textbooks for a New York publishing house. When the US entered WWII he gained a commission in the Navy as a Lieutenant Commander and was subsequently posted to the Solomon Islands as a Naval Historian. It was his experiences here that formed the basis of his first book, Tales of the South Pacific- submitted anonymously to his previous employers - which was published in 1947. After the war, Michener returned to editing textbooks, but the success of Tales of the South Pacific, which is actually a collection of 19 stories, detailing the everyday lives of officers and enlisted men - and women - seemingly stranded in the limbo of a South Sea Island paradise until the War, all to soon, catches up with them, would lead to Michener winning the Pulitzer Prize.

Tales of the South Pacific sent Michener's life off into a completely different direction. Continuing to travel the world, he became a prolific writer, producing more than forty novels, including Hawaii, Space, Centennial, The Bridges at Toko-Ri and Sayonara, many of which were made into successful films. He was awarded The Medal of Honour by President Gerald Ford in 1977. James A. Michener died on 16th October 1997.

|

Josh Logan |

Joshua Logan

Born in Texarkana, Texas on 5th October 1908, Joshua Lockwood Logan III attended Culver Military Academy, Indiana and then Princeton, where he formed the University Players with Henry Fonda and James Stewart. Graduating in 1931, he studied Method acting under Konstantin Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre for a short time before making his Broadway debut in 1932. By the mid 30s he was more involved with directing rather than acting, and in 1936, Logan was invited to work in Hollywood by producer David O. Selznick on The Garden of Allah, as dialogue director. He followed this with two films for Walter Wanger, History is Made at Night (1937) and I Met my Love Again (1938), before returning to direct for the theatre, somewhat disillusioned by Hollywood.

Logan’s stage career was interrupted by military service in England during WWII, in the US Army Air force Combat Intelligence division, but in 1945, he was able to resume his writing and directing career with memorable Broadway productions such as Annie Get your Gun, Mister Roberts, Picnic and – crossing the path of James A. Michener - South Pacific, sharing a Pulitzer Prize for the latter with Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein.

|

Marilyn Monroe in Bus Stop |

When John Ford fell ill during the filming of Logan’s play, Mister Roberts (1955), he reluctantly returned to Hollywood to co-direct (uncredited) the production with Mervyn LeRoy, who would share screen credit with Ford. Shortly after, Logan was hospitalised with a bi-polar disorder, a condition that had troubled him for several years. Uncertain as to whether he would be able to resume his career, he was persuaded to return to the world of film, when Harry Cohn asked him to direct the screen version of his earlier stage success, Picnic (1956), for Columbia. In the same year, he would direct Bus Stop for 20th Century-Fox. A second association with James Michener came the following year with the screen version of his novel, Sayonara, for Warner Bros., and on into 1958 with South Pacific for Magna and 20th Century-Fox.

Logan would continue to alternate between stage and screen for the remainder of his career, with such notable films as Tall Story (1960), Fanny (1961), Ensign Pulver (1964) – a non too successful film built around a character from Mister Roberts – followed by Camelot (1967) and Paint Your Wagon (1969). These two latter films, both major productions, were considered critical and commercial failures at the time of their release, but have remained popular with the public over the years. In 1977, Logan presented a revue called Musical Moments, in which he and his wife, Nedda Harrington, performed hit songs from his shows

From 1983 to 1986, he taught theatre at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

Joshua Logan died from supranuclear palsy on the 12th of July 1988.

From book into play

The transformation of a book into a play or a musical is not always straightforward, and can sometimes become mired in the personal foibles of those involved. Tales of the South Pacific was a prime example of that. In late 1947, Logan was working in partnership with producer Leland Hayward, and they were about to begin rehearsals for their stage production of Mister Roberts. Before throwing themselves into what would become a smash-hit show, they decided to take a brief holiday in Florida with their respective wives (In Hayward’s case, his soon-to-be-wife, Nancy Hawks). Before they left for Florida, they attended the opening of the stage version of A Streetcar Named Desire, which starred an electrifying young actor named Marlon Brando.

During an after-show supper, Logan began chatting to an old friend, Kenneth MacKenna, who was a story editor at MGM. They were discussing the forthcoming Mister Roberts, when MacKenna said, “There’s this other book set in the Pacific, you know – we’ve just turned it down. In fact most of the other studios have passed on it as well, but you might get something from it – some colour for Mister Roberts, perhaps”

“What is it?” Logan said, just to be polite, as he didn’t feel they needed any more ‘colour’ for Roberts.

“It’s called ‘Tales of the South Pacific’”, he said. “It’s by James Michener”.

The book and its author were unfamiliar to Logan, but he promised to have a look at it and next day bought a copy for the trip to Florida.

The following evening in their Miami Beach suite, Logan was flicking through the pages, and became captivated by one of the stories, ‘Fo’ Dolla’

|

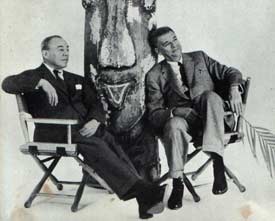

Leland and Josh |

The next day, after breakfast, Leland Hayward, noticing that Logan had been engrossed in the book, asked him if it was any good. “Oh, you wouldn’t be interested”, he replied casually. However, curiosity aroused, Hayward waited until Logan was dozing and stole the book off his lap and read it from cover to cover. When Logan woke, he found Hayward reading the last page.

“Where’d you get that?” Logan asked.

“Well, I knew you were tired, Josh”, said Hayward. “So I though I’d help you out by reading it – and we’re going to buy this son of a bitch!”

“So what are we going to do with it?” Logan asked.

“How the hell do I know?” Hayward exploded. “Maybe a couple of movies or straight plays – even a couple of musicals. We’d better buy it quick, before somebody else does – and no blabbing to anyone until the deal is settled!”

“Rodgers and Hammerstein would be perfect”, said Logan.

“Of course they would”, agreed Hayward. “But don’t you dare mention it to them. They’ll want the whole goddamn thing. They’d gobble us up for breakfast!”

Logan, reluctantly, agreed not to mention it, but while being delighted that his partner saw the potential in Michener’s book, he felt that Hayward was being unnecessarily cautious in his attitude to Rodgers and Hammerstein. Some time went by, with, frustratingly, no further action on Tales, so that when Logan met up with Richard Rodgers at a party, he could not resist the temptation to share his enthusiasm for Michener’s book with the composer, in spite of his promise to Hayward. Taking the composer on one side, Logan told Rodgers, “ Don’t tell anyone I told you this, but I own a story that you might make a musical of.” Feeling slightly ashamed that he had broken his word to Leland, he nevertheless found it hard to suppress the feeling of excitement as Rodgers took out a pen and note pad and wrote down, in his businesslike way, ‘T of the S. Pacific’ and the recommended story, ‘Fo’ Dolla’

More weeks went by, and by this time Logan and Hayward were deeply immersed in ironing out the problems of staging Mister Roberts. After a short run in New Haven, the critics seemed happy with the new production – in spite of it’s dirty words – and it moved to Philadelphia, where Richard Rodgers saw the first matinee there. He told Logan that he thought it was one of the best shows he’d ever seen, and then left for New York. But the evening performance was seen by Oscar Hammerstein, and chatting to Logan after the show – after making a few, what Logan described as ‘niggling suggestions’, Hammerstein went on to say that, “Dick and I can’t find anything to do next.”

Instantly alert, Logan said, “Didn’t Dick tell you about Tales of the South Pacific?”

Hammerstein said that he hadn’t, whereupon Logan suggested that he read a copy as soon as he could.

A couple of days later, Logan received a telephone call from Hammerstein. “Josh, you’re right, that Michener book is wonderful. When I mentioned it to Dick, he said, ‘Oh, I was crazy about it, too, but some son of a bitch I met at a cocktail party owns it, so we haven’t got a chance.’ I asked, ‘Was that son of a bitch Josh?’ and he said, ‘Logan! That’s the son of a bitch!’”

|

Mitzi and husband, Jack Bean, |

With Rodgers and Hammerstein hooked, Logan knew he would have to tell Hayward what he’d done – and he had a fair idea of what Hayward’s reaction would be.

“Bastard – you idiot bastard. You couldn’t have told them about it! You’re a decent human being. You couldn’t do that to me – or yourself!”

“I knew it was dangerous, but I couldn’t help it.” Logan said, trying to calm his irate partner. “They wanted a show. I was scared I’d lose them.”

“But Jesus, Josh, we haven’t finished negotiating the rights! With their power, they’ll have us over a barrel!”

This was confirmed the following day, after Hayward had spoken to Rodgers and Hammerstein. A sombre and angry Hayward informed Logan, “They won’t do it unless they own fifty one percent to our forty nine, which assures them of the final say, and us no say. All this, thanks to you.”

“I realize that, Leland. But let’s give it to them. They’re not the fairest – but they are the best.”

“Josh, you can’t, you simply can’t”, implored Hayward. “These stories are our property. You and I found them. We mustn’t give anything away – certainly not the controlling share. There are other composers – let’s go get someone else.”

But such was Logan’s, almost adolescent, worship of Rodgers and Hammerstein, that he forced Hayward to give them the final say on the proposed production. It was a decision that Logan knew was foolhardy even as he pressed Hayward into agreement, and never forgave himself. And, he suspected, Hayward never really forgave him, either.

And thus, South Pacific was born.

From play into film

The story that Logan and Hammerstein crafted from Michener’s tales was actually quite controversial for 1940’s audiences. Dealing with inter-racial romance, in the Lt. Cable and Liat sequences; the older man/younger woman relationship, with de Becque and Nellie; and even bigotry, with Nellie’s shocked reaction to de Becque’s mixed race children. Heady stuff for a musical play, in those days, and it is a tribute to the integrity of the adaptation that it does not flinch from these thorny subjects. The song, ‘Carefully Taught’, in which Lt Cable sums up his feelings about how his romance would be perceived by his family, back home, was removed from the original stage version, much to Hammerstein’s irritation, but would be restored in the 1958 film. Another restoration would be ‘My Girl Back Home’ – another song for Cable – which was removed from the stage version merely to trim the running time.

The 1958 screen version of South Pacific, while containing all the essential elements of the stage show, which had opened at the Majestic Theatre, New York on 7th April 1949, was, in many ways, quite different. One obvious difference, of course, is that in a film production – and particularly in the case of one which has been planned as a large-scale, big-budget musical extravaganza – scenes and action pieces that are merely referred to in dialogue on stage, can be played out for all to see. An example of this would be in the Thanksgiving show, in which Nellie Forbush sings the song ‘Honey Bun’ to an audience of soldiers and sailors. On stage, a few actors representing the military audience ‘spill’ off the stage and mingle with the theatre patrons, essentially making the theatre audience part the audience Nellie is singing to. In the film, however, hundreds of GIs and sailors – genuine military personnel, in fact – can be seen.

Another difference would be the fact that this version would be actually filmed in the South Pacific locations described in Michener’s novel.

|

Rogers & Hammerstein |

For some years, Rodgers and Hammerstein had wanted to film their smash-hit show, South Pacific, but were somewhat cautious after their other great musical stage show, Oklahoma!, had fared less well than expected at the box office. They blamed director Fred Zinnemann for this, so when they decided to film their south seas war musical, they naturally turned back to the director who’d originally staged the show with such great success: Josh Logan.

But Logan was equally cautious. Much had changed for the director in the years since his original involvement Rodgers and Hammerstein. In the early fifties, after his uncredited stint as director on John Ford’s film version of Mister Roberts, his continual battle with depression, and his bi-polar disorder, had led to him being hospitalised for a while.

He had been convinced his career was over, when Harry Cohn – head of Columbia Pictures – persuaded the shaky Logan that he was the man to direct their film version of William Inge’s Picnic – a previous Logan stage success. Somewhat stunned, by Cohn’s faith in him, he accepted nevertheless – and Picnic was a huge hit for Columbia. It also meant a resurgence of his career, and his success for Columbia was soon followed by another hit, this time, for 20th Century-Fox, with Bus Stop (1956), which starred Marilyn Monroe, and a second Michener adaptation for Warner Brothers, Sayonara (1957), with Marlon Brando and James Garner.

Hammerstein, Skouras & Logan |

When the suggestion that he might direct South Pacific was made by Hammerstein, Logan remembered, all to well, the bitterness that surrounded the production of the stage version several years previously - and the way he had been denied author’s royalties, even though he’d co-written it with Hammerstein. To make matters worse, George P. Skouras, president of Magna, who were co-producing the film with 20th Century-Fox, wasn’t even sure who Joshua Logan was - until he was appraised of the box-office returns of Logan’s previous films. Even then, Logan was offered a smaller fee for directing South Pacific than he’d received for Picnic.

Logan made it clear to Hammerstein that he wasn’t prepared to direct South Pacific on Skouras’ terms. “Putting a masterwork like South Pacific up on the screen is a huge responsibility, so I will only do it if I share in its profits,” Logan told Hammerstein. “I’m sorry, but otherwise, I’ll be forced to do something else.” To his surprise, they agreed his terms, and a generous profit-sharing deal was worked out. This would prove to be a shrewd move for Logan, as South Pacific would gross nearly $37,000,000 in 1958, alone.

When Logan and Hammerstein began to construct the stage version of South Pacific, back in 1948, Logan’s idea had been to use the ‘Fo Dolla’ tale as the basis of the plot, and make Lieutenant Cable, his lover, Liat, the beautiful native girl, and her mother, Bloody Mary, the focus of the story. But Hammerstein was drawn to the tale, ‘Our Heroine’, which told the story of a navy nurse, Nellie Forbush, and her romance with an older man, the French plantation owner, Emile de Becque – a story that was considered so low-key, compared to the rest of the tales, that it was omitted from original paperback edition of the book. Many people who saw the stage version wondered where they’d got the idea for these characters.

In addition, characters and scenes from three other tales were added – in particular the one featuring the coast-watcher who reports by radio on the movements of the Japanese fleet. Hammerstein also asked Michener for some more comic material, and he came up with a complete story about the sailors’ laundry arrangements, which gave more background for the Luther Billis character.

But now, with an estimated budget of around $6,000,000, and a decision to shoot practically the entire film on location – in Todd-AO – the original play could be expanded to include scenes and action that would never have been possible within the confines of a theatre stage. Another bonus was the co-operation of the US Department of Defense, in supplying men and equipment and permitting the filming of naval manoeuvres, involving thousands of men and part of the Pacific Fleet.

Playwright, Paul Osborne, whom Logan had been working with at that time, was brought in to create the new script, which would open out the play and take advantage of the exotic locations and additional facilities that were now available. Logan, Rodgers and Hammerstein now had to decide on the cast.

Casting

Ultimately, only two of the original stage cast would make it into the film version, Juanita Hall and Ray Walston. Juanita Hall had created the Tony award-winning role of the devious Tonkinese merchant woman, Bloody Mary, in the Broadway production. Ray Walston had performed the role of Luther Billis in the London and touring companies of the production.

|

Mary Martin |

But the biggest surprise was the omission of Mary Martin, in the role she had made famous, as Nellie Forbush. In a way, this was unavoidable, since the death of Ezio Pinza, in 1957. The two had made such an indelible impression on the public in the roles of Nellie and Emile de Becque, that it was though more practical to cast two completely different actors as the central characters of the story.

At one stage, Audrey Hepburn was considered for the role of Nellie, though probably the most startling choice was Elizabeth Taylor, with much encouragement from her husband, Mike Todd. Logan agreed; and Taylor, it seems, did have a pleasant singing voice, but was so overcome with nerves when auditioning for Richard Rodgers, that she could barely make a sound. Doris Day was also considered, briefly, but it was thought that the public would see her as simply Doris Day and not Nellie Forbush – and besides, she was too expensive for Fox, who were trying to keep the lid on their already extravagant budget. Day was actually quite keen to play the role, as she had not had a hit film since The Man Who Knew too Much, in 1956. But the following year, the release of Pillow Talk, would successfully revitalize her career. Eventually, contract player, Mitzi Gaynor, convinced Logan and Rodgers that she was Nellie, after testing twice for the role.

|

Mitzi Gaynor |

Rossano Brazzi had impressed Hammerstein, Rodgers and Logan with his performance opposite Katherine Hepburn in the 1955 film, Summertime, and seemed ideal for the part of de Becque. Unfortunately, Brazzi thought he would be using his own voice in the film, and was increasingly irritated by having to lip-synch the lyrics of his character’s songs to the voice of gifted opera star, Giorgio Tozzi. “This goddam cheap shit voice, I cannot sing to it!” Brazzi exclaimed at one point. Logan would eventually take the disgruntled star on one side and point out that no lip-synching means no continuing participation in the film. Brazzi ceased his protests, forthwith.

Brazzi was not the only actor to have his singing voice replaced, either. Juanita Hall was stunned to find that she would have to lip-synch to the voice of Muriel Smith, who had played Bloody Mary in the London production. Similarly, John Kerr – who would prove to be amazingly adept at lip-synching - in the role of Lieutenant Cable, had his voice dubbed by Bill Lee, who had sung the famous ‘Lonesome Polecat’ number for brother Caleb in MGMs Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). Lee would go on to provide Christopher Plummer’s singing voice, in The Sound of Music, in 1965. In the ‘Nothing like a Dame’ number, the rich, bass voice of the sailor, ‘Stewpot’ – played by Ken Clark – was provided by Thurl Ravenscroft, the voice of Tony the Tiger in the popular Kellog’s Frosted Flakes television commercials.

Logistics

The main shooting of South Pacific took place on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, with some four weeks of preliminary shooting in the Fiji Islands – the latter providing the backgrounds for the mystical island of Bali Ha’i. Four shiploads of technical equipment and a crew of two hundred arrived to join the huge cast of actors and dancers, the latter whom were already hard at work rehearsing the complex musical numbers under the direction of Leroy Prinz. Thousands of square feet of concrete roads and landing areas were built, as were extensive warehouse facilities, to house the many tons of camera and lighting equipment, costumes, vehicles, construction and catering equipment – the latter providing more than 75,000 meals throughout the duration of the production. Then, at the end of shooting, all the buildings and concrete had to be removed, including John de Cuir’s extensive military and Hawaiian sets, and the landscape returned to its original form. Meanwhile, back in Hollywood, four vast sound stages were fully occupied with the comparatively few indoor scenes – one of which housed a four hundred thousand dollar recreation of the Boar’s Tooth Ceremony, which was never actually used in the finished film – whilst another housed Alfred Newman, and a 125-piece orchestra, who were creating the magnificent score – with additional music – which would complement the impressive images that were being recorded on film, thousands of miles away.

|

"I'm in Love with a Wonderful Guy" |

Photography – and those colour filters!

More than 200,000 feet of 65mm film was exposed in the Todd-AO cameras that were used to photograph South Pacific. The cinematographer chosen to capture the spectacular beauty of the South Sea Islands was veteran Leon Shamroy – a real character in the film industry, and one known for his unflinching bluntness. When he was ready to start shooting a scene, and the actors were required on set, he would usually announce it by saying: ”I’m ready for the bastards, now”. So it was with some trepidation that Logan approached Shamroy with his idea.

|

Kim Novak and William Holden |

Logan did not really like Technicolor; he thought it made the sky too blue, the grass too green and flowers to look like cake decorations. He had persuaded James Wong Howe to use a rose tinted filter to soften the colours in the ‘Moonglow’ scene in Picnic. Shamroy was curious; “What’s this cocksucking idea you’ve got about colour?”

Logan explained that he wanted to create a similar effect to the one that they’d had in the stage version. Before each song, the stage lighting would change colour, before fading almost to black, when side spotlights would surround the character with a golden light, and a pin spot would concentrate on the singer’s face. At the end of the song, the lighting would return to normal.

“And what the fuck do you expect me to do about that?” an unimpressed Shamroy said. “You can’t take light away from a real sky just because someone starts singing – and you can’t make a cut and change the lighting because people will think it’s four hours later. What the hell do you want to change things for, anyway?”

“Well, Leon”, Logan persisted. “I really don’t know. I just feel that to have the same vivid Technicolor blue sky, the same sun, the same beach – well, it might just be a little overpowering for a whole film”. I was maybe hoping that we could treat the film in some daring way – but if you don’t know how to do it, I’m sure I don’t”.

|

|

| Bloody Mary sings to Lieutenant Cable...about mysterious Bali Ha'i | |

Shamroy still thought this was fantasy – and film was about reality – but he thought about it for a while (Shamroy had actually used filters before, to create the eerie effect in the House of Death sequence in The Egyptian) and then said, “There used to be some old bastard who’d done a great paint job on some moving filters. He could sneak a different colour into a scene and no one could figure out how he’d done it. Maybe we could get him to make some tests for us.”

They had some filters made and tested, but Shamroy still thought it would be safer to shoot each filtered scene normally as well. Logan agreed, and got the go ahead from producer Buddy Adler, at Fox, to duplicate these scenes. But after a couple had been shot, Adler flew in from Hollywood and told them that there was no need to shoot two versions of the scenes, as the lab had informed him that they could restore the normal colour in the printing process, if the scenes didn’t work. Logan wasn’t convinced, and called Shamroy over, who said, ”Don’t you think it’s safer to carry on what we’re doing?”

“No safer, according to the lab”, said Adler. “And besides, it doubles the expense of the whole location while those scenes are being shot. You don’t want to be responsible for that, Shammy”.

“I don’t want to be responsible for anything”, said Shamroy, and went back to his lighting.

What Adler hadn’t told Logan was that the leaching process would take three months – and was expensive. After nine weeks of shooting, the film wrapped and Logan flew back to New York to direct a play, Blue Denim, and left instructions for the lab to keep the colour down. He didn’t see a complete cut until many months later – and was horrified at the sight of what he thought were garish colour changes. Logan begged Skouras to let him take the film back to the lab and get the colour changes removed, but he refused. “We got previews booked in ten days”, he said. “We can’t cancel them now. Besides, it’s your fault, you made the picture cost too much - now I got to get my money back!”

In spite of the colour changes – and many people, it must be said, don’t mind them at all, including this writer – the film was a huge success. South Pacific was the most financially successful film Logan would ever make. Released on March 19th, 1958, it was warmly received all over the world and especially so here in England, where it enjoyed a record-breaking 231 week run at the Dominion Theatre, in London. In that theatre alone, it made enough money to pay of the entire production cost of the film. The Academy Award-winning soundtrack would remain among the top ten albums in the U.S. for the next two years. According to the booklet, which accompanies the re-mastered CD release of the album, Mitzi Gaynor received more money in record royalties than she was paid for appearing in the film.

South Pacific remains a remarkable cinematic achievement. An outstanding musical from an era of outstanding musicals, its success would not be equalled in that decade. And it would only be Rodgers and Hammerstein who would surpass it, several years later, with The Sound of Music, in 1965.

|

Billis and Bloody Mary |

I’ll leave you with one more Leon Shamroy anecdote, in which he succinctly sums up the rigours of filming in exotic locations, far from the reassuring facilities of the studio. Attempting to film Cable and Billis’ landing on Bali Ha’I, they had the Todd-AO camera set up on a cutter that had been supplied by the Navy. Hundreds of extras lined the quarter mile of beach that was to represent the mysterious Bali Ha’I, all prepared to throw their colourful leis and bunches of flowers as a welcome to their guests. The sailor assigned to the cutter started the engine, and off they went towards the shore. Everything was perfect, and Logan expected to get the shot on the first take. Just then, the motor conked out, and they just drifted around, bobbing up and down on the waves. A mechanic came out, but after tinkering with it for a few hours told him, “I‘ve been trying to fix this thing all night – I guess the Navy just sent you a lousy cutter!” A Navy mechanic was sent for as hundreds of people stood around. By the end of the day he said, “Why don’t you make the Navy give you a decent boat – this one’s kaput.” A new cutter was provided the next day, and they got the shot – and everyone got two days’ pay instead of one. Shammy said, with the voice of experience, “I learned a long time ago. Never trust a fucking boat.”

Researching this article gave me a lot of pleasant reading. The most useful – and most entertaining - were Joshua Logan’s two autobiographical books, My Up and Down and In and Out Life, for the stage stuff, and Movie Stars, Real People and Me for the films. Great fun. I also used The Tale of South Pacific, published by Lehman Books in 1958. Ed.

Opening shot - the PBY |

|

|

Filming on the terrace of De Becque's plantation |

|

|

Billis and Cable on Bali Ha'i |

|

|

Todd-AO camera dolly |

Mitzi in the 'Honeybun' number |

|

"There is Nothing Like a Dame" |

|

|

South Pacific in Liverpool, 1959 |

|